Verdun Battlefield Visit, Verdun, France

18 September 2012

by

Lynn E. Garn, Ph.D.

The battle for Verdun was one of the most significant battles of World War I, which was fought from 1914 to 1918, mainly between the Allies, led by the United Kingdom, France and Russia, fighting against the Central Powers, led by Germany and Austria-Hungary. However, many other countries were involved including the United States, which entered the war in 1917.

Verdun was significant to the French in World War I because it was near the border with Germany and was one of the largest French cities near Germany. It also was in a region of France that has lots of natural resources that the Germans hoped to gain use of. It became part of the German war plans when a German general concluded that an attack against Verdun could be waged by the Germans without much cost to Germany but that it would be costly for the French to defend Verdun. The general was also convinced that the French would spare no expense in defending Verdun, which, he argued, would weaken them to the point that the French could be defeated in a "War of Attrition."

The battle for Verdun began on 21 February 1916 and lasted eleven months. It was mainly between Germany and France. It was one of the deadliest battles of World War I with an estimated 3/4 million casualties. Both sides stubbornly insisted on frontal assaults in an attempt to overrun the enemy positions. Each assault resulted in a lot of men killed. Some of the assaults were successful. However, positions rarely were strong enough to be held for long. The tactics used by the commanders wasted soldiers and shifted most lines back and forth only short distances over the course of the battle. Some positions were known to have changed over a dozen times during the battle.

One of the things that made the battle so costly in terms of casualties was the trench warfare employed by both sides. Although the futility of an army attempting to overrun a well‑armed, entrenched enemy using foot‑soldiers armed only with rifles and bayonets should have been evident from the results of Pickett's Charge in the American Civil War, both sides regularly attempted to overrun enemy trenches in World War I.

To make matters worse, the last major battles fought between the combatants prior to World War I were in the Franco‑Prussian War in 1870‑1871. In the time following that war, technology changed significantly and military tactics failed to keep up, making trench warfare even more costly than in earlier wars. Barbed wire, significantly more lethal artillery, machine guns, and poison gas made it easy to defend a position against mass attacks. As a result, many soldiers were killed when one side attempted to take land defended by entrenched troops.

Another factor that increased the number of casualties was the strategy employed by both sides known as a "War of Attrition." Both sides must have thought they could win a War of Attrition, were slow to re-evaluate their approach and stubbornly continued sending men against entrenched troops. Both hoped to wear down the other side and both were willing to lose a few of their own in hopes of killing more of the enemy.

World War I was also the last time trench warfare was used extensively in combat. Near the end of the war the British introduced tanks that were unaffected by enemy machine guns and other defenses used by soldiers in trenches. The tanks could run over trenches. So trench warfare became impractical and did not play the same role in World War II as it had in World War I.

In 2007 Stan and I and our wives visited Normandy, France, to see some of the World War II battle sites. At the time we were aware that Verdun, France, was the site of a famous and bloody battle during World War I. And we sort of set a goal to someday visit the battlefield. As we were planning our trip to Europe, we decided to include Verdun on our agenda.

In order to get the best tour possible, Stan contacted Martin Galle, a German Tour Guide, who gives tours of European battlefields. Stan had been on a tour of Normandy with him before our above mentioned trip to Normandy. And Stan knew Martin would give us a good tour. Martin maintains a web site with information about some of the battlefields, which is at Martin Galle's Web Site. Although the site appears to deal with Normandy, he is knowledgable about other battlefields all over Europe.

I can't say enough about how much extra information and clarification Martin was able to add to our tour. He provided extra, interesting details on several occasions that we wouldn't have heard or understood without him. Also, I'm sure we would have spent lots of time trying to navigate among destinations. He made sure we didn't get lost. Finally, there were several interesting things that we would never have found, such as the Langer Max or big gun site, the museum at Romagne, the village destroyed by mine explosions and the house with all of the bullet holes in it. The day was truly memorable.

The first place that Martin took us was the site of a big gun used by the Germans. The

Germans had a number of big guns that were originally intended for use on battle ships. These

guns were known as the 38 cm SK L/45 "Max", SK - Schnelladekanone (quick-loading cannon) L -

Länge or Langer Max for short. Langer Max translated means Long Max. At some point the

Germans decided to use the guns on land. And at the first site where Martin took us, we could

see the remnants of the gun emplacement and shells used in the gun.

Stan Beside Langer Max Shell

Me Beside Langer Max Shell

These shells were 15 inches in diameter. The barrels of the guns from which they were shot

were 52 feet long.

The picture below shows the pit that was built as part of the fixed gun emplacement

the Germans built for the Langer Max outside Verdun.

Fixed Gun Position For Langer Max Gun Outside Verdun

Stan and I were both amused at several signs of the way they had built the site or how they may

have left in a hurry. Apparently they left some sacks of concrete on the ground, which hardened where

they lay and were never tampered with after the Germans abandoned the site. The picture below shows

some of the sacks of hardened concrete. World War I ended 95 years ago. So the concrete

shown in the picture is at least 95 years old. The paper holding the concrete has long ago worn away.

Sacks Of Concrete Left Where They Hardened

The GPS coordinates of the remnants of the gun emplacement discussed above are

49.359318N, 5.605466E. Click on the coordinates to see the location on

Google Maps.

The next place that Martin took us was the Azannes II German Cemetery. There is also an Anzannes I Cemetery that we did not visit. This cemetery is truly unique when compared to cemeteries for Americans who die overseas in war. Azannes II is a German cemetery on French soil. The Germans put their cemetery on the soil of their enemy. Although the United States has cemeteries in several countries in Europe, all of the our cemeteries are in countries that were allies of the United States during the war. None of the U.S. cemeteries in Europe is in Germany, our enemy during World War I and World War II when American soldiers died in war and were buried in cemeteries overseas. The German Azannes II cemetery in France is a bit like the United States placing a cemetery on the island of Okinawa or Iwo Jima during World War II. So Azannes II is unique when it comes to the way the United States creates cemeteries for our war dead.

The picture below is of Stan and our guide, Martin Galle, at the entrance

to the Azannes II cemetery. Crosses on the graves may be seen in the background.

Martin Galle and Stan At The Entrance To Azannes II Cemetery

The plaque or sign below denotes in both German and French who is buried in the cemetery. The

inscription translates to:

with the years 1914-1918 added between the two different language versions.

|

| Plaque Denoting Who Is Buried In The Cemetery |

One of the curious differences between Germany's army in World War I and

World War II is the inclusion of Jewish soldiers in the German army in

World War I. During that war there was no exclusion or persecution of Jewish

soldiers. They fought in World War I just like other German citizens. The two

graves below are just two of many markers for Jewish soldiers in the cemetery.

Grave Marker For Willy Löwenstein

Grave Marker For Alex Franken

One may notice the similarity of the name of the second Jewish soldier to the well known

American comedian and Senator from the State of Minnesota. We have all heard claims that dead

people have been "allowed" to vote in U.S. elections to steal an election. Is this grave

marker evidence that Minnesota elected a dead man as Senator in 2008? No, they are definitely

two different people. However, I would love to know if the Senator is somehow related to this soldier.

One of the grave markers that we came across was that of an Oskar Galle. Since he had the same

last name as our guide, we had to have our guide's picture with the marker. Martin was not aware of

any relationship to the dead soldier.

Martin Galle Beside Marker For Soldier Named Oskar Galle

The picture below is of me beside one of many similar markers that were erected to various units

of German soldiers that fought at Verdun. The inscription reads, "Zu Ehren Der Gefallenen Kameraden,"

followed by what appears to be the abbreviation for a particular unit. The German above loosely

translates to, "To Honor The Fallen Comrades."

Me Beside A Marker For Soldiers

The GPS coordinates of the Azannes II Cemetery discussed above are

49.305902N, 5.474921E. Click on the coordinates to see the location on

Google Maps.

The next place we went was the burial site of Lieutenant Colonel Émile

Driant and the bunker or defensive position that was named after him. Lt. Col. Driant

was the highest ranking casualty of the battle around Verdun. When artillery and

infantry were removed from his area of the battlefield, he criticized the move. Not

long afterward, the position was overrun by the Germans despite desperate efforts by

Lt. Col. Driant and his men. Shortly after Lt. Col. Driant ordered his men to withdraw

from their positions, he was killed. The Germans, out of respect for military tradition

and his rank buried him with full military honors. The French later moved his body to

near where he was killed. The picture below shows

the defense works near where he was buried.

Defensive Position Near Burial Site Of Lieutenant Colonel Émile Driant

The picture below shows a monument for Lieutenant Colonel Émile Driant.

Monument For Lieutenant Colonel Émile Driant

The picture below shows the back side of the monument for the grave of Lieutenant Colonel

Émile Driant. Note that the path to the road through the trees behind the marker is almost

a tunnel.

Back Side Of Monument For Lieutenant Colonel Émile Driant

The GPS coordinates of the Driant monument discussed above are

49.271571N, 5.405527E. Click on the coordinates to see the location on

Google Maps.

The next place that Martin took us was to Verdun's Bayonet Trench. This is the place where a company of French soldiers was buried with their bayonets protruding out of the ground above them. It was believed at the time that the men were buried by the artillery fire during the heat of the battle while still in the trenches with bayonets pointing upward as if to repel the enemy that might approach the trench. The story was heard by a Mr. Rand of the United States, who funded the construction of a memorial to the brave French soldiers in the trenches.

After the memorial was built, other theories sprung up about the possible reasons for the

unusual burial of the men in the trench. However, no one knows for sure what actually caused

the almost simultaneous deaths of the men in the trench and the unique burial they received. The

picture below shows the entrance to the monument over the area where the trench was found.

Monument To The Soldiers In Verdun's Bayonet Trench

The picture below is a monument placed by the French Ministry of Veterans and War Victims at

the Bayonet Trench.

Monument At Bayonet Trench

The inscription is in French and translates as: The Memorial of the Trench of Bayonets has been

designed at the end of the war to guard intact this famous strip of land where heros were buried with

their guns protruding. The mission of the Ministry of Veterans and War Victims is to ensure the

maintenance of these sacred places.

The picture below is a view down the length of the trench through the mounuent built over it.

When originally built, the area of the monument over the trench, shown here, included bayonets protruding out of the ground much as they were when the trench with the buried soldiers was first discovered. However, in the intervening years scavengers have broken off the bayonets and stolen them for souvenirs or for other reasons. Alert visitors may still see nubs of the bayonets protruding from the ground.

View Of Trench Area

The GPS coordinates of the Bayonet Trench discussed above are

49.213308N, 5.426148E. Click on the coordinates to see the location on

Google Maps.

The next place that Martin took us was Fort Douaumont, the largest and highest fort built

by the French to protect Verdun against the Germans before World War I. At some point the

French General Staff concluded that their forts around Verdun could not withstand bombardment

from the large guns that Germany had. As a result, they partially disarmed the fort. In early

1916, three days after the beginning of the Battle of Verdun, a small force of Germans attacked

the fort and took it over from the French without a fight. This shocked the French and was

undoubtedly embarrassing. Although the French managed to recapture the fort months later, it

was occupied by the German army for much of the Battle of Verdun. The picture below shows the approach

to the entrance of the fort.

Fort Douaumont

The picture below shows one of the long halls or tunnels built into Fort

Douaumont.

Underground Hall At Fort Douaumont

The picture below shows one of the areas where soldiers slept while stationed

at Fort Douaumont.

Sleeping Area At Fort Douaumont

The picture below is a small cross that commemorates a large group of German

soldiers who were killed when gunpowder they were working with exploded. Care had to

be taken continually to insure that there was no static electricity or sparks that

might ignite the gunpowder. Men at this location in Fort Douaumont were killed

when the powder was ignited accidentally.

Memorial To German Soldiers

The inscription on the cross above is in German. The inscription at the top is something

like: The Dead Comrades. The inscription at the bottom of the cross says: German War Graves

Commission.

The picture below is of the top of Fort Douaumont and some of the towers that held

artillery that could be directed at the enemy.

View Above Fort Douaumont

The GPS coordinates of Fort Douaumont discussed above are

49.215719N, 5.438783E. Click on the coordinates to see the location on

Google Maps.

Along the road with which we approached and returned from Fort Douaumont there was

a series of trenches that were used by the soldiers. On our return from the fort, we stopped

to get a better look at them. The photo below shows a section of the trench with Stan on the

right.

Trench Near Fort Douaumont

The pictures below are of Stan and me in one of the trenches near Fort Douaumont.

Me In Trench Near Fort Douaumont

Stan In Trench Near Fort Douaumont

Near Fort Douaumont is a cemetery and memorial known as the Fort Douaumont

Ossuary, where Martin took us for our next stop on the tour. The picture below shows the

cemetery with the tower of the Ossuary in the background. The trees around the cemetery

give a misleading impression of the size of the Ossuary, which extends both directions

behind the trees for some distance.

Fort Douaumont Ossuary and Cemetery

The picture below is the inside of the Ossuary. The walls have the names of soldiers who died nearby in battle. On the right one may see what looks like brown boxes with slanted edges. These cover the bones of soldiers and civilians who died on the battlefields nearby.

During and after the battle, a doctor who lived in the area became involved in identifying

remains found on the battlefield when people started bringing him remains in hopes that he could

identify them. Over time he became the person to whom all remains found on the battlefield were

taken. As he collected more and more remains, he started grouping them according to where on the

battlefield the remains were found. Each of the brown boxes on the right in the picture below has

the remains of victims that the doctor collected from a different part of the battlefield.

View Inside The Fort Douaumont Ossuary

Along the back wall and a floor below each of these boxes in the Ossuary is a window to the

outside. Through this series of windows one may see the bones that have been stored under each

brown box in the photo above.

The photo below shows the remains stored under one of the brown boxes in the Ossuary.

Remains Of Verdun Victims

The picture below shows more remains of victims of the battle in and around Verdun.

Remains Of Verdun Victims

Another thing that one may see inside the Ossuary is stories that highlight the

lives of some of the soldiers who survived World War I. One of the soldiers so highlighted

was Frank Buckles, an American Soldier who was born in Missouri. At the time his story

was included at the Ossuary, he was still living. Frank Buckles became the last surviving

American veteran of World War I. He died on February 27, 2011 at the age of 110 years,

26 days. The picture below shows a corner of the poster board with his story.

Frank Buckles Story

The picture below is of Frank Buckles, the last surviving American veteran of World

War I. He is holding a picture of himself taken when he was in the army. This picture is posted

in the Ossuary as part of the Frank Buckles story.

Frank Buckles In Later Years Holding A Picture Of

Himself As A Soldier

The GPS coordinates of the Fort Douaumont Ossuary discussed above are

49.20829N, 5.423917E. Click on the coordinates to see the location on

Google Maps.

The next place that Martin took us on our tour was a French fort, Fort Froideterre, near the

Fort Douaumont Ossuary. Fort Froideterre was one of several similar forts that the French built on

the outskirts of Verdun to repel the Germans. The picture below shows one of the towers above the fort.

Tower At Fort Froideterre

The picture below shows a close-up of the impact area of artillery that hit the

tower.

Close-up Of Fort Froideterre Tower

The GPS coordinates of Fort Froideterre discussed above are

49.197648N, 5.403626E. Click on the coordinates to see the location on

Google Maps.

The next stop on our tour was Fleury-devant-Douaumont, the site of a village that was destroyed during the war. It was one of several villages that were abandoned during the war and were never reoccupied after the war. In the case of Fleury-devant-Douaumont I believe people were prevented from reoccupying it because of the fear that unexploded artillery might kill people who tried to move back to the area.

Fleury-devant-Douaumont was at the center of some of the fiercest fighting during the war. Both sides occupied the village many times. It is claimed that it was captured and recaptured 16 times. Since this area was fought over so fiercely, it was the target of a lot of artillery. Martin told that records show how much artillery was directed toward the area. Using the approximate area into which the artillery was directed and the number of rounds of artillery, I calculated that one round of artillery hit approximately every one and a half square yards of land. Anyone in the area had to be in a trench or had to have some sort of protection or they would surely become a victim.

The picture below shows a memorial chapel that was built to commemorate the

village, villagers who were driven away by the war and the victims who died there.

Fleury-devant-Douaumont

The picture below shows the ground around Fleury-devant-Douaumont. Notice the

evidence of artillery impacts.

Ground Around Fleury-devant-Douaumont

The GPS coordinates of Fleury-devant-Douaumont discussed above are

49.198276N, 5.429311E. Click on the coordinates to see the location on

Google Maps.

Less than a half mile to the southeast of Fleury-devant-Douaumont is the Verdun

Memorial, a museum with information about the war and some artillery and equipment used

during the war. The picture below shows some of the artillery on display in front of the

museum. One can see Stan and Martin on the at the right in the picture.

Artillery At The Verdun Museum

The picture below shows a wagon that was introduced to the battle by the Ameicans.

The design was particularly useful for maintenance of roads. A nearby sign read: American

Field-Wagon used for maintenance and repairs of roads during the victorious offensive of

the French and American Forces in Meuse-Argonne from September 26 to November 9, 1918.

American Field Wagon

The GPS coordinates of the Verdun Museum discussed above are

49.19497N, 5.43359E. Click on the coordinates to see the location on

Google Maps.

Proceeding southeast from the Verdun Museum about half a mile, one comes to an intersection. On one corner of the intersection is the monument shown in the picture below. The monument has been called the "Wounded Lion," and marks the point of closest advance of the German troups in their attack on Verdun.

It has been suggested that the monument refers to the Lion of Bavaria, a symbol

of Bavaria and that the French used a wounded version of the lion for the monument

to show victory over the Lion of Bavaria.

Wounded Lion

The GPS coordinates of the Wounded Lion Monument discussed above are

49.192082N, 5.437324E. Click on the coordinates to see the location on

Google Maps.

About half a mile southwest of the Wounded Lion Monument is a monument to André Maginot,

which was placed there in honor of the man who convinced the French to build a set of forts

along the French border with Germany after World War I. Many have heard of the Maginot Line built by

the French and the equivalent, the Siegfried Line, built by the Germans before World War II. Maginot

served in the French army during World War I and was wounded, resulting in his walking with a limp

for the rest of his life. Although the idea for the Maginot Line was not actually his idea, he was

such a strong proponent of the line that the French named it in his honor. The picture below shows the

monument erected in Magiinot's honor near Verdun.

Monument to André Maginot

The GPS coordinates of the monument to André Maginot discussed above are

49.187005N, 5.431445E. Click on the coordinates to see the location on

Google Maps.

The next place we visited was the Montfaucon American Monument located in the ruins of the

former village of Montfaucon. The monument towers 200 feet above the former village. It commemorates

the actions of the American army that forced the retreat of the enemy. The picture below shows

the monument.

Montfaucon American Monument

The picture below shows a view of the back side of the Montfaucon American Monument through the

ruins of the former village that was once on the site.

Another View Of The Montfaucon American Monument

The GPS coordinates of the Montfaucon American Monument discussed above are

49.272355N, 5.141748E. Click on the coordinates to see the location on

Google Maps.

The next place that we visited was the Meuse American Cemetery located to the south of

Romagne-sous-Montfaucon. It is said to be the largest American cemetery in Europe. The picture below

shows the pool and terraced area between two large pieces of ground that contain the graves of 14,246

soldiers including 486 unknown soldiers.

Pool And Terrace In Meuse American Cemetery

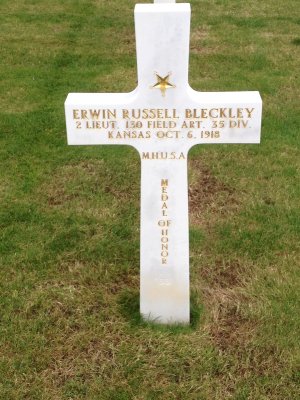

We came upon two markers for Medal of Honor recipients in the cememtery. The photos

below are of the grave markers. Notice the rows of graves behind the marker on the left.

Marker For Freddie Stowers Of South Carolina

Marker For Erwin Russell Bleckley Of Kansas

The picture below shows a view of the rows of graves in the cemetery as viewed from the

terraced area.

Rows Of Graves

The picture below is another view of the terrace. Martin and I are walking

on the terrace on the left side of the picture

Martin And Me On The Terrace

The picture below shows the flags of various countries in the cemetery building.

Flags At Meuse American Cemetery

The GPS coordinates of the Meuse American Cemetery discussed above are

49.334142N, 5.089735E. Click on the coordinates to see the location on

Google Maps.

The next place that Martin took us was to a museum in Romagne, called Romagne '14 - '18.

The '14 - '18 in the name of the museum refers to 1914 to 1918, the years that World War I was

fought. The museum is full of lots of interesting artifacts that have been recovered from the

battlefields around Verdun. The picture below shows guns that were collected on the battlefield.

Guns Collected On The Verdun Battlefields

An interesting thing we discovered at the museum is that artifacts are still very easy to

find all over the battlefield today, 95 years after the war ended. And the owners of the museum

add to their collection regularly. On the day that we visited the museum, the owners were just

returning with artifacts they had recovered from a field that had been plowed the day before. We

were told that they never follow the plows as the soil is being tilled for fear of being hit by

unexploded ordnance that the plow might set off when the ordnance is disturbed by the plow. They

wait a day after a field is plowed before searching it for artifacts. It was interesting that

even after 95 years the soil brings up new artifacts each time it is tilled.

The picture below shows canteens and cookware collected on the battlefield.

Canteens And Cookware Collected On The Verdun Battlefields

The picture below shows a cobbler's bench, shoes, and shoe-making equipment found

on the battlefield.

Cobbler's Bench And Shoes

The picture below shows a helmet, medals, and other artifacts found on the

battlefield.

Helmet, Medals, And Other Artifacts

The picture below shows the frame of a man-powered generator. The generator itself

has been removed. The generator was turned by two men riding the "bike" to turn the

sprocket that pulled the chain and turned the generator.

Frame Of Man-Powered Generator

The GPS coordinates of the Romagne '14 - '18 Museum discussed above are

49.332097N, 5.083413E. Click on the coordinates to see the location on

Google Maps.

On our way to Varennes, discussed below, we passed the house shown in the picture below. This house, recently occupied, still bares evidence of the battle that was waged for Verdun during World War I. One can see many bullet holes in the siding that have been there since the war ended 95 years ago. On the right side of the picture one can see that the density of holes is about one hole per square foot.

It was amazing to see this house in the French countryside, complete with bullet holes,

to know that it has been occupied almost all of the intervening 95 years since World War I,

and to know that it has changed very little since the war ended.

House With Bullet Holes In Siding

Unfortunately we did not get the GPS coordinates of this house.

The next place that Martin took us was Varennes, the site of a monument erected

by the Pennsylvania Monuments Commission to honor the troops who served in World War I, or

The Great War, as it was known shortly afterward. The picture below shows the monument

that was erected in 1927.

Pennsylvania Monument To Soldiers Of World War I

The picture below is a close-up of the inscription on the Pennsylvania Monument to

soldiers of World War I.

Close-up Of Inscripton On Pennsylvania Monument

The picture below is another view of the Pennsylvania Monument to the soldiers of World

War I.

Another View Of The Pennsylvania Monument To Soldiers Of World War I

The village of Varennes is most

famous to the French because it is where French King Louis XVI, his wife

Marie Antoinette, and their immediate family were captured in June 1791 when they attempted to

escape from Paris and the French Revolution. It was claimed that someone recognized the king's

resemblance to the picture of the King on a coin he attempted to use to buy something

and alerted people in the neighboring villages that the King might be trying to escape.

The King and his family were apprehended as they passed over a bridge in Varennes and were returned to Paris where the rest is history. King Louis XVI was beheaded with a guillotine about 19 months after his aprehension in Varennes as one of he victims of the French Revolution. His wife Marie Antoinette, was also beheaded with a guillotine about two and a half years after being captured. And their son, the crown prince, was placed in prison where he died four years after being captured without ever being crowned King of France even though royalists referred to him as King Louis XVII and his uncle, the brother of King Louis XVI, skipped XVII when assuming the crown as next in line and called himself King Louis XVIII.

As we were leaving Varennes, we passed over the bridge where the King and his family were apprehended.

The GPS coordinates of Varennes discussed above are 49.226158N, 5.031437E. Click on the coordinates to see the location on Google Maps.

The final place that Martin took us is the abandoned village of Vauquois. Like Fleury-devant-Douaumont

discussed before, Vauquois was destroyed during the war. However, Vauquois was destroyed more by explosions

of gunpowder in tunnels below the lines than by artillery fire from above. The picture below shows a monument

to the village.

Monument To Vauquois

One of the tactics used by both the French and German combatants at Vauquois was to tunnel

under the enemy lines and set off explosives. This is simmilar to the tactic used by a Pennsylvania

Regiment during the American Civil War at the siege of Petersburg 50 years prior to World War I. We

don't know if the inspiration for the tactic at Vauquois came from the actions of the Pennsylvania

Regiment or if it was dreamed up independently. Either way, the tactic destroyed the village. The

picture below shows a sign at a fence around the rim of one of the craters at Vaquqois. The English

part of the sign reads, "German Mine Of 14th May 1916, 60 Tons Of Explosives, 108 Dead Of The 46th I.R."

The message is repeated in German and French. Behind the sign one can see part of the crater that

was created by the explosion.

Sign At Crater Created By Mine Explosion

The picture below is a view from below of the crater discussed above. On the rim of the

crater and located horizontally in the middle of the picture, one may see the sign that is shown

in the previous picture.

View Of The Crater From Below

The picture below shows the entrance to one of the tunnels used to dig under the

enemy lines at Vauquois.

Tunnel Entrance At Vauquois

The picture below shows narrow gauge railroad cars that were used at Vauquois to

haul equipment to and from the troops and into the tunnels.

Narrow Gauge Railroad Cars At Vauquois

The picture below shows a different view of the Vauquois Monument that was shown

above. This view is across a different set of craters than the ones shown above.

Vauquois Monument And Craters

The picture below shows still another view of the Vauquois Monument from a different

perspective with a different set of craters in the foreground.

Vauquois Monument And Craters

The trenches around Vauquois are considered to be among the best remaining examples

of the trenches used at Verdun in World War I. The picture below shows one of the trenches

at Vauquois.

Trench At Vauquois

Vauquois also has lots of examples of the defenses that were used around the lines. The

picture below shows the barbed wire that was placed above one of the trenches to slow an

enemy attack on the soldiers defending the trench.

Trench And Barbed Wire Protecting The Trench

The picture below shows another example of defensive measures used during World War I.

These spikes are around one of the craters and may not have actually been there while the

battle was going on. They probably were placed there as a barricade to keep people from

falling accidentally into the crater. However, the spikes are from World War I and were

undoubtedly actually used at the Vauquois region of the battle.

Spike Barricade Along Crater

The picture below shows another excellent example of the trenches around Vauquois.

Trench At Vauquois

The two pictures below show me in the trenches at Vauquois.

Me In A Trench At Vauquois

Me In A Trench At Vauquois

The GPS coordinates of Vauquois discussed above are

49.204224N, 5.068183E. Click on the coordinates to see the location on

Google Maps.

I mentioned earlier that one of the values of having Martin as our tour guide was the additional information that he was able to provide us. One interesting piece of additional information he provided was an opinion on an experience that our Uncle Howard Nixon had and wrote about in his story about his experiences during World War II.

Uncle Howard wrote that shortly before the start of the Battle of the Bulge, he and another soldier were invited by some girls to a house near Malmédy, Belgium, to play cards. When they got there, they found the girls' parents and also, surprisingly, a young man about 25 years old. The young man just stood there with his hands folded behind his back and never said anything. After a while Uncle Howard got suspicious and thought, "What's a young guy like that doing there?" Uncle Howard thought that he might be a German spy and they excused themselves and left the house. The part of Uncle Howard's story that discusses this event may be found at the top the page here.

Upon hearing the story, Martin Galle suggested that the young man may have been a Belgian soldier who had been conscripted by the Germans and had escaped by deserting. Martin said that young men were forced to fight for the Germans against their will and when they deserted, the SS often took it out on the families of the deserters. This was how they kept the conscripted soldiers from deserting. However, as soon as the home towns of the conscripted soldiers were liberated, the threat of harm to the soldiers' families was no longer credible. At this point the soldiers, upon hearing that their home towns had been liberated, frequently deserted.

This was the case for soldiers who had been born German as well as soldiers of other nationalities that the Germans conscripted. Martin said that his own grandfather, a Colonel in the German army, and a German citizen, deserted at the end of the war when he learned that the allies had occupied his town. Upon desertion, Martin's grandfather returned home and immediately surrendered to some American soldiers who occupied the town.

The point of all this is that the young man that Uncle Howard saw could also have been a family member who had returned home when he learned that the Americans had liberated Malmédy. However, Uncle Howard's story makes it clear that he was convinced that the young man was a German spy.

All in all I felt as though Martin Galle gave us an excellent tour. I would gladly take another tour with him. He added a lot of extra information at each stop that we didn't read on any of the signs that explained the various sites.

To contact me by mail, write:

Mr. Lynn E. Garn

12210 Redwood Ct.

Woodbridge, VA 22192-1611

USA

Or email me at:

Updated on 15 February 2013